«Шоссе в Никуда» («Lost Highway»)

Год выпуска: 1997

Режиссер: Дэвид Линч (David Lynch)

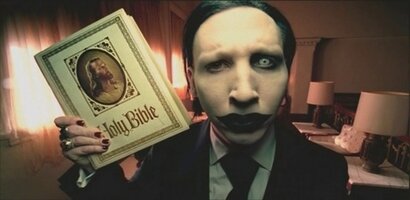

Мэрилин Мэнсон — Порнозвезда #1

Твигги Рамирез — Порнозвезда #2

«Королевы убийства» («Jawbreaker»)

Год выпуска: 1999

Режиссер: Даррен Штейн (Darren Stein)

Мэрилин Мэнсон — The Stranger

«Боулинг для Колумбины» («Bowling for Columbine»)

Год выпуска: 2002

Режиссер: Майкл Мур (Michael Moore)

«Боулинг для Колумбины» — документальный фильм американского режиссёра и политического активиста Майкла Мура. Фильм посвящен проблеме свободного владения оружием в США. Центральная тема ленты была посвящена исследованию причин трагедии 20 апреля 1999 года в школе «Колумбина», в небольшом городке рядом с Денвером, где двое подростков расстреляли 13 человек. СМИ утверждали, что виной послужило влияние жестоких компьютерных игр и музыки Мэрилина Мэнсона, которой, по их мнению, интересовались убийцы. Как выяснилось позже — они не были поклонниками группы. Несмотря на это, «охота на ведьм» пошатнула карьеру артиста. В фильме Мэнсон дал небольшое интервью. Примечательно, что эпизод был снят за кулисами, перед концертом группы в Денвере, в 2001 году — спустя два года после трагедии.

«В прокат с водилой: Обогнать дьявола» («The Hire: Beat the Devil»)

Год выпуска: 2002

Режиссер: Тони Скотт (Tony Scott)

Мэрилин Мэнсон — в роли самого себя.

«Клубная мания» («Party Monster»)

Год выпуска: 2003

Режиссер: Фентон Бэйли, Рэнди Барбато

Мэрилин Мэнсон — Кристина

«Цыпочки» («The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things»)

Год выпуска: 2004

Режиссер: Азия Ардженто (Asia Argento)

Мэрилин Мэнсон — Джексон

«Вампирша» («Rise»)

Год выпуска: 2007

Режиссер: Себастьян Гутиеррес (Sebastian Gutierrez)

Мэрилин Мэнсон — бармен

This ambiguity is useful, because it turns any discussion of this subject into a debate over semantics. Really, though, Gamergate is exactly what it appears to be: a relatively small and very loud group of video game enthusiasts who claim that their goal is to audit ethics in the gaming industrial complex and who are instead defined by the campaigns of criminal harassment that some of them have carried out against several women. (Whether the broader Gamergate movement is a willing or inadvertent semi respectable front here is an interesting but ultimately irrelevant question.) None of this has stopped it from gaining traction: Earlier this month, Gamergaters compelled Intel to pull advertising from a gaming site critical of the movement, and there’s no reason to think it will stop there.

In many ways, Gamergate is an almost perfect closed bottle ecosystem of bad internet tics and shoddy debating tactics. Bringing together the grievances of video game fans, self appointed specialists in journalism ethics, and dedicated misogynists, it’s captured an especially broad phylum of trolls and built the sort of structure you’d expect to see if, say, you’d asked the old Fires of Heaven message boards to swing a Senate seat. It’s a fascinating glimpse of the future of grievance politics as they will be carried out by people who grew up online.

What’s made it effective, though, is that it’s exploited the same basic loophole in the system that generations of social reactionaries have: the press’s genuine and deep seated belief that you gotta hear both sides. Even when not presupposing that all truth lies at a fixed point exactly equidistant between two competing positions, the American press works under the assumption that anyone more respectable than, say, an avowed neo Nazi is operating in something like good faith. And this is why a loosely organized, lightly noticed collection of gamers, operating from a playbook that was showing its age during Ronald Reagan’s rise to power, have been able to set the terms of debate in a

$100 billion industry, even as they send women like Brianna Wu into hiding and show every sign that they intend to keep doing so until all their demands are met.

The simplest version of the story goes something like this: In August, the ex boyfriend of an obscure game developer writes a long, extensively documented, literally self dramatizing, and profoundly deranged blog post about the dissolution of their relationship. Among his many accusations, he claims she slept with a gaming journalist in return for favorable coverage. This clearly isn’t true, but a group of gamers becomes convinced there is a conspiracy to not cover this story. The developer’s personal information is distributed widely across the internet, and she and a feminist gaming activist receive graphic, detailed threats, forcing the activist to contact the police and flee her home. In response, several sites publish think pieces about the death of the gamer identity. These pieces are, in essence, celebrations of the success of gaming, arguing that it is now enjoyed by so many people of such diverse backgrounds and with such varied interests that the idea of the gamer a person whose identity is formed around a universally enjoyed leisure activity now seems as quaint as the idea of the moviegoer. Somehow, this is read to mean that these sites now think gamers are bad. The grievances intensify, and the discussions of them on Twitter are increasingly unified under the hashtag gamergate.

In August, a programmer named Eron Gjoni posted a long account of the end of his relationship with Zoe Quinn, an indie game developer; it was regrettable and embarrassing for everyone involved. At the time, Grayson freelanced for Kotaku and for a popular gaming site called Rock Paper Shotgun; later, he would join Kotaku as a full timer. Gjoni’s post was taken as evidence that Quinn had slept with Grayson in order to receive a favorable review for one of her games,

Depression Quest, at Kotaku.

Released in early 2013,

Depression Quest is a choose your own adventure style game about managing life with depression, released independent of the big gaming studios and promoted as a boutique product. It was the right kind of game, made by the right kind of person, to hold up as evidence of the broadly correct and generally appealing notion that games and gamers are diversifying in new and increasingly unexpected directions, and so Depression Quest was lauded by several outlets as a brave and personal piece of work. This was, strictly speaking, true; the structural gamification of dealing with depression directly was novel and earnest, and it was and remains a game that might induce serious thoughts about a serious subject. It was also true, though, that Depression Quest was not a good game so much as a critic proof gesture at one, seeming to exist more as a set of instructions for the writing of puff pieces about how brave its creator was than anything else.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the game and its glowing reception were

hugely unpopular among a certain type of video game fan. By late 2013, when Quinn added the game to Steam’s Project Greenlight, she had become the target of sustained and virulent harassment.

Once Gjoni’s breakup post was made public, with its

sotto voce intimations of sex for coverage exchanges, this cycle was set back into motion and supercharged. It’s important to note that the initial claim that sparked Gamergate was not only untrue, but totally nonsensical neither Grayson nor anyone else even reviewed the game at Kotaku, and while Grayson did write about Quinn in late March in a feature about a failed reality show, that was before they’d begun their romantic relationship. Nevertheless, fevered accusations that Quinn had traded sex for press began to float around online, and Quinn’s sexual history and nude photos were spread around 4chan and IRC. The general premise was that it is pointless to talk about «gamers» as a whole the constituency is too vast and further, that the core identity of a «gamer» had become dominated by the loudest and most unacceptable sort. The most openly prosecutorial was a Gamasutra op ed by editor at large Leigh Alexander titled «‘Gamers’ don’t have to be your audience. ‘Gamers’ are over.» It argued that the only way to begin anew the project of defining the culture of gaming is to tear the whole thing down and build from scratch. It contained this passage:

Gamergate is surprisingly well organized, with «operations» staged from a mishmash of Reddit boards, infinite chan threads (having abandoned 4chan), and unofficial official dedicated sites. «Daily boycotters,» for example, are instructed not just to email targeted companies to express their grievances, but to spam these targets on Sundays and Wednesdays to maximize congestion shit up the Monday morning rush, and dogpile in the middle of the week, so the mess has to be addressed before the weekend. They’re told never to use the actual term «Gamergate,» as that will allow the message to be filtered.

This has proved effective enough to get Intel to keel over, and it won’t be surprising if it works on other companies, too. A representative of one of the companies targeted by the daily boycotts said that they’d received about 1,000 emails so far, more than half of which were pro Gamergate. The only comparable online flare up any of the representatives interviewed could remember is SOPA the

Stop Online Piracy Act, one of the most universally panned pieces of legislation in recent memory. This is how a very few people can get their way, and the use of this technique is one of the many similarities between Gamergate and the ever present aggrieved reactionaries whose most recent manifestation is the Tea Party.

This isn’t a complex jump. Like, say, the Christian right, which came together through the social media of its day little watched television broadcasts, church bulletins, newsletters or the Tea Party, which

found its way through self selection on social media and through back channels, Gamergate, in the main, comprises an assortment of agitators who sense which way the winds are blowing and feel left out. It has found a mobilizing event, elicited response from the established press, and run a successful enough public relations campaign that it’s begun attracting visible advocates who agree with the broad talking points and respectful enough coverage from the mainstream press. If there is a ground war being waged, as the movement’s increasingly militaristic rhetoric suggests, Gamergate is fighting largely unopposed.

The default assumption of the gaming industry has always been that its customer is a young, straight, middle class white man, and so games have always tended to cater to the perceived interests of this narrow demographic. Gamergate is right about this much: When developers make games targeting or even acknowledging other sorts of people, and when video game fans say they want more such games, this actually does represent an assault on the prerogatives of the young, middle class white men who mean something very specific when they call themselves gamers. Gamergate offers a way for this group, accustomed to thinking of themselves as the fixed point around which the gaming industrial complex revolves, to stage a sweeping counteroffensive in defense of their control over the medium. The particulars may be different, and the stakes may be infinitely lower, but the

dynamic is an old one, the same one that gave rise to the Know Nothing Party and the anti busing movement and the Moral Majority. And this is the key to understanding Gamergate: There actually is a real conflict here, something like the one perceived by the Tea Partier waving her placard about the socialist Muslim Kenyan usurper in the White House.

There is a reason why, in all the Gamergate rhetoric, you hear the echoes of every other social war staged in the last 30 years:

overly politically correct, social justice warriors, the media elite, gamers are not a monolith. There is also a reason why so much of the rhetoric amounts to a vigorous argument that Being a gamer doesn’t mean you’re sexist, racist, and stupid a claim no one is making. Co opting the language and posture of grievance is how members of a privileged class express their belief that the way they live shouldn’t have to change, that their opponents are hypocrites and perhaps even the real oppressors. This is how you get St. Louisans sincerely explaining that Ferguson protestors are the real racists, and how you end up with an organized group of precisely the same video game enthusiasts to whom an entire industry is catering honestly believing that they’re an oppressed minority. From this kind of ideological fortification, you can stage absolutely whatever campaigns you deem necessary.

When Blizzard revealed the trailer for Warlords of Draenor, its newest World of Warcraft expansion, at a showcase in Los Angeles last month, it opened with the sort of ritual auto fellatio familiar to anyone who’s ever attended any corporate event. What was odd about it or at least what would be for anyone unfamiliar with the peculiar folkways of the gaming industry was Blizzard’s choice of a master of ceremonies. There was Chris Watters of GameSpot, one of the largest gaming sites on the internet, standing on a conference stage sponsored heavily by GameSpot being broadcast to video game fans on GameSpot’s bandwidth and carrying GameSpot’s logo, hyping a trailer for a game that he had never played was still in development.

If the goal of Gamergate is to wipe out corruption in games journalism if the movement isn’t merely a bunch of loosely shaped sublimated qualms about feminism and minorities it’s doing a shit job of identifying the actual, honest to god problems in games writing. It’s not as if those problems are hard to see.

As a rule, games journalism is inherently compromised. From the top down, publishers ranging from AAA behemoths like Electronic Arts to the IndieCade crowd do in fact enjoy symbiotic relationships with gaming media outlets, and if it came down to nothing more than sex and petty corruption, that would be nice, because the problem would certainly be a lot more easily solved.Articles Connexes: